It's Been A Long Struggle

Supreme Court Rules In Favor Of Same-Sex Marriage Nationwide

~ June 26, 2015

~ Click here for the story on the L.A. Times website ~ by Russ Allison Loar ~ 8-5-1996

© All Rights Reserved

Juneteenth ~ Say what?

Happy Juneteenth, however we white people may or may not celebrate it. Of course the Emancipation Proclamation was about two and a half years earlier. Can you imagine being a slave in Texas when one day Union troops come to town saying black folks are free?

“Says who?” asks a suspicious black man.

“Why none other than President Lincoln,” a Union officer responds.

“But I heard someone say Lincoln was shot dead?”

“Well, Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation before he died.”

“When did he do such a thing?” the perplexed black man asked.

“Well, actually, it was about two and a half years ago,” the Union officer sheepishly answered.

“Two years ago? Why in the hell did it take so long to let us know? Here we’ve been free for more than two years and nobody bothered to tell us?”

“Sorry about that,” the Union officer apologized, tipping his hat while signaling to his men the need for a quick exit from what was an increasingly embarrassing situation.

~ © All Rights Reserved

Uber Al Fresco

The comfort of a limo with the thrill of a convertible. Caution is advised when reclining seats while vehicle is making sharp turns in busy intersections. Not recommended for freeway driving.

~ Words and Photo by Russ Allison Loar

© All Rights Reserved

Poetry Class

“Nothing beats an 18-year-old pair of hips.”

It’s from a poem. Her poem. That blond-haired girl in my college creative writing class, reading her poem out loud, a poem about her love of sex, of having sex, preferably with lean 18-year-old boys at the zenith of their sexual energies.

Within a few days of her recitation I noticed she began coming to class with the professor, a man not quite twice her age who evidently was quite willing to submit his hips to her critical assessment.

Yes, they had definitely paired off, but unfortunately, the academic quarter came to an end before she had a chance to construct a poem about this new sexual experience.

But why should I let that fact limit my own imagination?

You Are Not My Daddy

Yes, you are not my daddy.

Yes, you are not my boyfriend.

Yes,

Yes,

Yes.

Oh my God,

Yes!

~ © Blond-haired College Girl

There’s nothing like a college education to expand one’s imagination.

© All Rights Reserved

Kids Need Discipline!

The school board Tuesday night unanimously approved

the death penalty for dress code violations.

~ by Russ Allison Loar

~ Photo by Paul and Lora Guajardos

© All Rights Reserved

You Did Not Return My Shovel

I really need it bad.

You left and took my shovel.

It’s made my life so sad.

It was my only shovel.

I had it all these years.

I own no other shovel.

My tool shed sheds such tears.

I can see it now,

Shining in the sun.

Glowing in the rain.

O my lost shovel,

Causes me such pain.

I am cold in the night

Cause my shovel’s not in sight.

How can I carry on

When my shovel’s lost and gone?

Someday when you’re in hell,

You’ll know the reason why.

You horked my beauty shovel,

And digging made you die.

~ Russ Allison Loar

© All Rights Reserved

Godspeed

In Jamestown,

My father's forefather,

Excised from country,

Bereft and starving.

(What an asshole!)

~ by Russ Allison Loar

~ U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist Seaman Matthew Bookwalter

© All Rights Reserved

Easter Brunch at the Country Club

~ Text & Jesus insertion by Russ Allison Loar

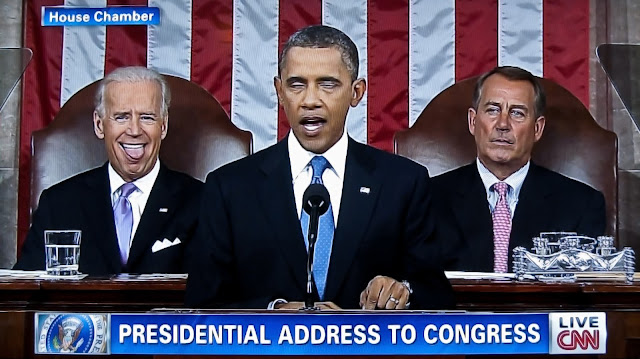

Biden Dorks Out

A Lie

I was playing with a baseball I’d found in my front yard when two older boys walked up to me.

~ By Russ Allison Loar

© All Rights Reserved

The Myth Of Unity

It is the clarion call of politicians: Life in America would be ideal if only we would all come together as one people and be unified and united,

~ by Russ Allison Loar

What Do You Really Think?

What do you really think?

No,

Not what you’ve heard,

Those predigested generalizations

Tailored to specific constituencies,

Foot soldiers amassing in the unity of certainty.

What do you think that’s genuinely yours,

Uniquely yours,

The product of your own ingredients,

Of your own mental exercise,

Unaltered by expectations of approval

Or disapproval,

Stripped of cliché,

Of second-hand observations . . .

Summon the truest voice within and tell me,

What do you really think?

~ Poem and Photo by Russ Allison Loar

© All Rights Reserved

Accumulation

Inside my box I kept:

1. A polished orange agate

2. A worn Canadian quarter with a moose on one side

3. A dark red matchbook from a fancy restaurant

4. A small magnifying glass in a black plastic frame

5. A brass pocket knife

6. A four cent stamp with Abraham Lincoln’s picture on it

7. A fingernail trimmer

I had a portable record player and a collection of 45 rpm records with pictures of the artists on the paper sleeves. Elvis! I had picture books of nursery rhymes, jungle animals, Peter Pan, automobiles, a school book with illustrations of Columbus discovering the new world, children’s poetry and comic books. I had baseball cards of the Los Angeles Dodgers. Sandy Koufax! I had a set of small rocks glued onto a cardboard mounting, each underscored with their names and geographic origins.

I had a half-dozen or so stuffed animals who shared my bed.

I had drawers full of inconsequential objects such as red rubber bands from Sunday newspapers, paperclips, a bottle of dried-up glue, spare change, pens and pencils, a ruler, a small plastic stapler and scattered staples, a Scotch tape dispenser, assorted notepads, folders, three-ring binders, old birthday cards, Christmas cards sent to my family and forgotten photographs taken when we were all dressed up for some holiday. We always had to face the sun “for the light,” but my baby blue eyes have always been very sensitive, so I am squinting like actor Clint Eastwood in all my childhood photographs. “You've got to ask yourself one question. Do I feel lucky? Well, do ya punk?”

I had plastic guns and rifles, dozens of small metal cars—Dinky Toys—with real rubber tires, and a few hastily glued model airplanes.

I had a closet full of clothing picked out by my mother and drawers of white and tight underwear, assorted socks that would not stay up and pajamas decorated with jungle beasts riding carousels. I had ancient pairs of worn tennis shoes and rarely worn dress shoes that made blisters on my heels.

I had a red and white Schwinn bicycle with large tires. I attached playing cards to the spokes to make the bike sound like a motorcycle. When I attached a balloon it sounded even better, but the balloon would soon pop.

So many possessions for such a young boy, and yet so few compared to this adult life where the clutter of so many years of accumulation dims the childhood wonder I had when everything was new. My first yo-yo, candy apple red. My first guitar, made of plastic. It would not stay tuned. My first record player. It came in a portable metal case. My first camera, a Kodak Brownie camera that I used to take fuzzy, oddly colored pictures of our cats.

So many possessions, year after year. Now it’s just so much stuff, gathering dust, waiting to be dispersed after I die, when I’m finally free from all these things.

© All Rights Reserved

In A Coffee Shop

In a coffee shop

~ by Russ Allison Loar

© All Rights Reserved

Teenage Renegade

It was not hard to be renegade in the sleepy Los Angeles suburb of West Covina during the 1960s.

Emerging from the conservative ‘50s,

all you had to be was a disagreeable teenager, especially in this

Anglo-Saxonite community where most of the local power brokers attended Rotary

Club pancake breakfasts with an alarming regularity. Come to think of it,

regularity was also a big deal during this era.

My home town was very much like

the place portrayed in the movie, “American Graffiti.” It was a teenage car

culture, and after I turned 16, I had a driver’s license. Not long after, I had

a car. My parents were upper middle class, so I did not have to actually earn

the money to buy a car. And my mother was eager to be free of having to take me

places, and then, pick me up and bring me home. Her life was busy enough, what

with Women's Club luncheons to plan, bridge parties, country club appearances

and the ongoing burden of supervising housekeepers and gardeners – all this along

with a husband who actually expected her to make dinner on a regular basis.

Yes, regularity was a pretty big deal during this era.

Nowadays there are lots of

restrictions on young drivers, but when I got my license, I was free, turned

loose on the streets without any restrictions or guidelines. Just a few hours

of driver’s ed. But I was a pretty good driver. I’d had experience, what with

all those times I took my parents’ cars out on the road when they were away for

a weekend trip. Yes, I remember learning how every intersection was not

necessarily a four-way stop as I propelled my mother’s lumbering, razor-finned

Cadillac straight toward a passing car who, much to my surprise, had no stop

sign. I hit the brake pedal just in time.

Then there was that lesson

about road rage, what we used to call, “mad” or “angry.” I thought driving was

a competition, and that the object was to beat the other drivers. After all, I

wasn’t actually going anywhere. So I jammed down the gas pedal and managed to

pull the great white whale in front of this other guy in an old, compact car

who had tried his best not to let me into his lane. While I was waiting behind

another car at a stop sign, he got out and walked up to my car, signaled for me

to roll down my window, which I did, then punched me in the face.

By the time I had my own car, a

dark green 1965 Ford Mustang – the fastback model – I was seasoned. I’d make my

car too fast to catch, and I certainly would never roll down my window again

for anybody.

In those days it seemed like most of my friends and rivals were working on their cars, customizing old Chevys, putting in big carburetors, high performance shifters, custom exhaust systems, giant racing slicks – even whole new engines. This was long before the state-mandated smog check. Nobody checked the condition of our cars when we renewed their registrations, so all modifications went undetected. I was not one of the more talented kid mechanics around, although I could gap a spark plug. I was a musician, a guitar player, and I did not like getting my fingers stained with grease. So I took the money I saved from teaching guitar lessons and working in a local pizza parlor and went to a speed shop in a neighboring city to let the experts juice up my horsepower. The first thing they did was rip out all the smog prevention equipment.

“You don’t need all this

stuff,” I remember the mechanic saying. Years later, when I tried to trade the

car in on a new model, the local Ford dealer would disagree. “You’ve got no

smog equipment! We’re going to have to replace it all just to put the car on

the lot.”

Oops!

Except for a little cash for

dating and guitar strings, I’d put all my money into my car – a nice racket for

the speed shop – and after a while I began racing my car on Saturdays at the

nearby Irwindale Speedway along with all the other high school amateurs. But as

a renegade teenager, the real thrill was street racing. It was like being a

gunslinger in the Old West, just prowling around town, looking to challenge

somebody to a shootout.

Yes, I had my share of speeding

tickets, but I was never caught racing. Most of us weren’t. There were not that

many police officers cruising around town in those days.

There was always the occasional

race during the day, when I’d just happen to pull up next to another kid in a

hot car after school. Who was faster? We just had to find out! But weekend

nights were the real prime racing time. It was like jousting, trying to prove

our nascent manhood to our girlfriends, or to somebody else’s girlfriend.

Sometimes the races were

organized.

Some guy with greasy hair had a

new Camaro 280z and swore he could take me. Bets were made and the next

Saturday night my friends blocked off both ends of a sleepy suburban street

about a half-mile long while we lined up our cars. About twenty high school

kids gathered at the finish line. Camaro boy couldn’t catch me, even though his

car may have been faster. I was always incredibly quick off the starting line.

That’s what won me the race set

up by the speed shop at Irwindale Raceway. There was another kid, a rich kid

whose father owned a shopping center, who was already out of high school, who

came to the speed shop with a Mustang pretty much like mine. The speed shop

mechanics figured this guy would be good competition for me. After they’d done

their best to expand his horsepower, we set a date.

The early part of the afternoons at Irwindale were spent doing practice runs, called “qualifying.” You had to turn a good enough time in your particular class to compete in the early evening, before the actual professionals did their stuff for the audience who sat in bleachers on either side of the quarter-mile track.

We both edged our cars into

starting position, our engines almost window-shatteringly loud because we’d

opened up our “headers” (high performance exhaust systems) to bypass the

mufflers. From experience, I knew the slight lag time of my car – from the time

I hit the gas pedal to the car’s forward surge – allowed me to start a half

second before the green light flashed.

We waited, then the first

yellow light flashed on, moving down toward the green light. The moment Rick’s

brain told him the light was green, I’d already jumped out from the starting

line. He was momentarily stunned, and even though he turned a faster time, he

never caught me. It wasn’t really about how fast you went, it was about who got

there first. Mind over horsepower. I made it to the finish line first, won the

trophy and renewed admiration from my girlfriend.

Yes, it was a moment.

Of course now as a responsible

adult I am appalled at my behavior, risking accident and injury on the streets

of my sleepy suburban town. Perhaps that’s why it made so much sense for all of

us to go just outside of town to the Chicken Ranch.

There was a long, straight road

inside the Chicken Ranch property, made for trucks to pick up eggs and

chickens, I suppose. Nobody stayed with the chickens at night, especially not

on Saturday nights. This particular night had not been the first time high

school hot rods had raced there, but it was my first time.

There were dozens of competitors from area high schools and junior colleges, and dozens more who just came to watch. It is a solemn testament to the short-range saturation of the teenage brain that none of us had entertained a single thought about potential consequences. Rubber burned and smoked and engines spit and roared as pair after pair of racers hurtled down the improvised racetrack. After I made my run, the growing chaos of beer-swilling youth amazingly enough triggered some fledgling sense of adult apprehension, and so I left. As I exited the entrance to the Chicken Ranch, I was passed by a long line of police cars.

That was the last race ever

held at the Chicken Ranch. It was my senior year, and before long, I’d own a

more practical car, have a more practical girlfriend, and grow a little less

renegade as the wild anarchy of my teenage years passed. After all, I had to

prepare for the wild anarchy of my twenties.

~ by Russ Allison Loar

© All Rights Reserved